Philosophy for Children (P4C)

Socrates said that “the unexamined life is not worth living” and anyone working or living with children will know that they are natural philosophers because they wonder.

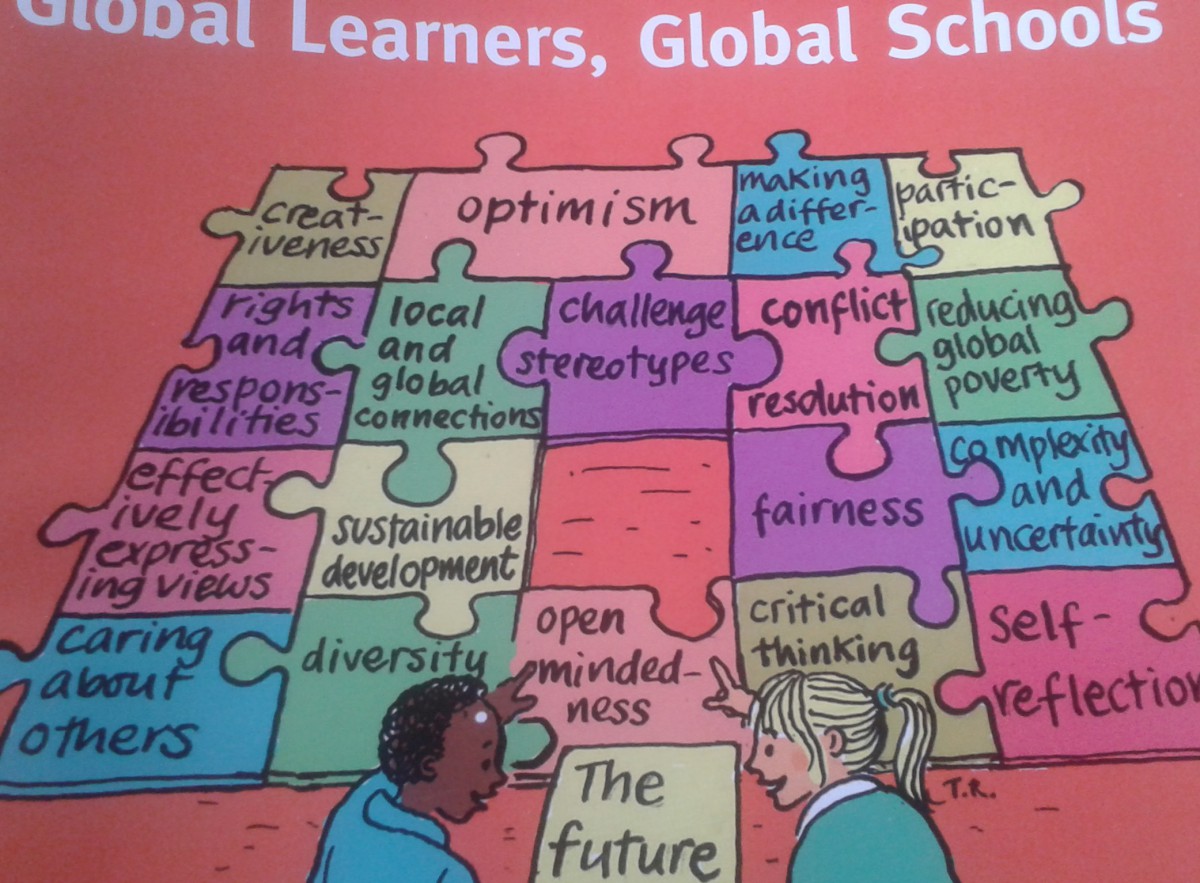

At CDEC we aim to develop global learning, and it’s concepts, skills, knowledge and values, through many pedagogies and practical activities, but have found increasingly that the SAPERE (Society for the Advancement of Philosophical Enquiry and Reflection in Education) Philosophy for Children (P4C) approach is one of the most popular and successful ways to achieve this. I have recently completed my Level 1 training and have been trialling a few activities and enquiries in schools and feel compelled to share my learning.

The main premise is that children can think deeply, and that our role as classroom managers is to facilitate a philosophical discussion, deepening it to develop a critical enquiry in a community forum. There are lots of stages and processes to ensure the experience for the children develops and deepens each time, and so that it is a safe environment for children to express themselves. Over the weeks, months and years starting from a young age (F2/Y1) children can and do develop the ability to discuss, resolve, debate, articulate and think. I have also seen videos of P4C being used with KS4 children, so it is relevant for any age group.

P4C emphasises The 4 Cs – Caring, Collaborative, Critical and Creative thinking. Teachers tend to need to work on the collaborative and caring thinking skills with their class before moving onto critical and creative thinking. Using each other’s names is a very simple yet powerful way of helping to embed this way of working – say who you are passing the ball to, for example. The Four Cs should also be discussed explicitly with children – what sort of question/comment is this? And they will start to recognise and identify whether things said are critical, caring, collaborative or creative, or a combination of any of these.

There are lots of games and activities teachers use to prepare their pupils for enquiry-based philosophical discussion, known as Community Builders – games that focus on developing trust, fairness, listening, sharing, asking and answering questions, and creative thinking, for example.

Concept stretchers are another way to deepen children’s thinking or to stimulate an enquiry – where do you stand on this issue/idea/concept? To what extent do you think pets understand what you are saying, for example. There are also numerous Thinking Games around to help deepen children’s thinking and ideas. This preparation may take several sessions or longer before the children are ready to undertake a full enquiry.

Children need to learn how to generate philosophical questions – questions that are open ended and which explore a concept; there are many activities designed to help facilitate this. A variety of stimuli, especially stories, images, film clips and artefacts are used to stimulate the children’s thinking and questions. It can take a long time for children to really focus on philosophical concepts, and on developing philosophical ideas and questions rather than descriptive ones that will simply evolve into a discussion, a short answer or a list of attributes, for example, rather than a deeper thinking enquiry.

The Enquiry really is democracy in action – the children sit in a circle, talk within agreed rules and procedures and democratically choose the question for the enquiry from a choice of their own questions generated from the stimulus. They can all share their opening thoughts, there is an equal opportunity for speech and reflection, and they all have the opportunity to express their final thoughts as well. All are allowed to agree or disagree with someone else or the question.

The role of the facilitator is hugely important, and so far in my experience the hardest aspect of the whole P4C process. You need to ensure that everyone gets to speak who wants to, but you also need to judge when to intervene in the enquiry, and crucially what to ask to move the discussion on. The more you do it, the more appropriate your prompts become. You also need to allow for silence and keep an eye on those who tend to dominate and those who say very little, and engineer less/more opportunities as appropriate. A facilitator can also ask the children to define the terms used in the question, either at the start or once the enquiry has got going – it may be helpful at a different point in time. The aim should be to be the guide at the side not a sage on the stage (Roger Sutcliffe). When asking questions, giving 3 seconds increases the quality of children’s answer hugely (lots of research evidence to support this).

Here are some Socratic Questions which help focus children’s thinking:

• Questions that seek clarification

• Questions that probe reasons and evidence

• Questions that explore alternative views

• Questions that test implications and consequences

• Questions about the question/discussion

The session ends with a group reflection on how the enquiry went, the skills used, the process rather than the subject matter. Again many tools and activities are available to support this.

There are so many ways P4C can enrich, enhance and support learning across the curriculum. With the teachers on the Level 1 course the other week we were literally able to apply the principles of the process to any subject, and I have seen some fantastic written responses in RE, Science, English, Geography and History to name a few, all stimulated by a philosophical, critical enquiry approach to subject content. The scope for supporting global learning, speaking and listening, developing vocabulary and statistics is huge.

My only regret is that I did not have this strategy to hand when I was in the classroom; my next aim is to find a school willing to allow me to develop P4C over a long period of time! I think it is such a powerful, thought-provoking, stimulating and empowering approach to learning.

“I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think.”

Socrates